Who Wears the Pants?

A Note from the Program of As You Like It

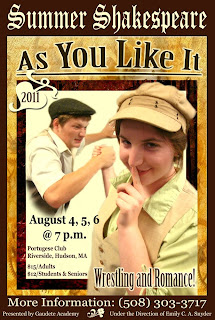

Performing at: The Portugese Club in Hudson, MA

Performing on: August 4-6, 2011 at 7 p.m.

In theatre, there are some actresses who may claim to specialize in “pants roles” – that is, an actress who is often cast as a man. This term makes less sense today, when everybody – male and female – wears pants almost exclusively. But when women were first allowed to act on the stage, in Europe and then eventually in England in 1660 (nearly fifty years after Shakespeare’s death), “pants roles” became all the rage. After all, if a woman put on pants…you could see her legs! It was very sexy.

Operas took advantage of “pants roles,” writing boy’s parts for mezzo-sopranos and altos whose voices more closely resembled pre-pubescents – not unlike the modern stage convention of having a woman play the title role of Peter Pan. The famous Spanish playwright, Lope de Vega, praised the new opportunity, saying, “a breeches role usually pleases [the audience] very much.” Shakespeare’s comedies became very popular due to this new fad... so much so that we’ve forgotten that the Bard originally wrote his pants roles…to be played by men.

Operas took advantage of “pants roles,” writing boy’s parts for mezzo-sopranos and altos whose voices more closely resembled pre-pubescents – not unlike the modern stage convention of having a woman play the title role of Peter Pan. The famous Spanish playwright, Lope de Vega, praised the new opportunity, saying, “a breeches role usually pleases [the audience] very much.” Shakespeare’s comedies became very popular due to this new fad... so much so that we’ve forgotten that the Bard originally wrote his pants roles…to be played by men.

Shakespeare uses the trick of a woman impersonating a man three notable times: Rosalind in As You Like It, Viola in Twelfth Night, and briefly at the end of The Merchant of Venice, Portia. In the original, a male actor had the task of impersonating a woman…impersonating a man. Shakespeare even winks at his casting restrictions in Rosalind’s epilogue when the actor says: “If I were a woman…!” which would have gotten a big laugh from Elizabethan audiences.

What a state is a modern actress in, then? It was quite easy for a male Orlando playing opposite a male “Rosalind” to act as though he believed his stage-love was a young boy…because it was. And it was easy for audiences to believe that Orlando wasn’t stupid or near-sighted for being confused by his “Rosalind’s” gender. In Shakespeare’s time, the play…played.

Nowadays, though, so many actresses who play Rosalind hope that their breeches will do most of the “manifying” for them. In those same productions, Orlando continues to be completely oblivious to the actress’ high voice and shapely form. The question must be asked: does the inclusion of female actors make As You Like It unplayable?

The answer is a resounding: “No!” There’s a reason Shakespeare is an acknowledged genius. For his text fully allows for multiple interpretations. Why couldn’t Orlando be much more suspicious, far less duped by Rosalind’s manly show? After all, Orlando seems to be constantly testing the boy “Rosalind,” calling him/her “pretty youth,” and finally giving him/her the ultimatum, “I can live no more by thinking.”

Nor is Shakespeare’s insight into women dated: in the modern age, women continue to struggle with pants roles – as single moms, as businesswomen, as women searching for some model other than a princess in pink. Women “still give the lie to their consciences,” putting on an aggressive “manly” mask to show the world. What, then, is the remedy? Love, Shakespeare replies. Love that sees beyond the mask, and makes it empowering to wear a dress.

Performing at: The Portugese Club in Hudson, MA

Performing on: August 4-6, 2011 at 7 p.m.

In theatre, there are some actresses who may claim to specialize in “pants roles” – that is, an actress who is often cast as a man. This term makes less sense today, when everybody – male and female – wears pants almost exclusively. But when women were first allowed to act on the stage, in Europe and then eventually in England in 1660 (nearly fifty years after Shakespeare’s death), “pants roles” became all the rage. After all, if a woman put on pants…you could see her legs! It was very sexy.

Shakespeare uses the trick of a woman impersonating a man three notable times: Rosalind in As You Like It, Viola in Twelfth Night, and briefly at the end of The Merchant of Venice, Portia. In the original, a male actor had the task of impersonating a woman…impersonating a man. Shakespeare even winks at his casting restrictions in Rosalind’s epilogue when the actor says: “If I were a woman…!” which would have gotten a big laugh from Elizabethan audiences.

What a state is a modern actress in, then? It was quite easy for a male Orlando playing opposite a male “Rosalind” to act as though he believed his stage-love was a young boy…because it was. And it was easy for audiences to believe that Orlando wasn’t stupid or near-sighted for being confused by his “Rosalind’s” gender. In Shakespeare’s time, the play…played.

Nowadays, though, so many actresses who play Rosalind hope that their breeches will do most of the “manifying” for them. In those same productions, Orlando continues to be completely oblivious to the actress’ high voice and shapely form. The question must be asked: does the inclusion of female actors make As You Like It unplayable?

The answer is a resounding: “No!” There’s a reason Shakespeare is an acknowledged genius. For his text fully allows for multiple interpretations. Why couldn’t Orlando be much more suspicious, far less duped by Rosalind’s manly show? After all, Orlando seems to be constantly testing the boy “Rosalind,” calling him/her “pretty youth,” and finally giving him/her the ultimatum, “I can live no more by thinking.”

Nor is Shakespeare’s insight into women dated: in the modern age, women continue to struggle with pants roles – as single moms, as businesswomen, as women searching for some model other than a princess in pink. Women “still give the lie to their consciences,” putting on an aggressive “manly” mask to show the world. What, then, is the remedy? Love, Shakespeare replies. Love that sees beyond the mask, and makes it empowering to wear a dress.

Comments

Post a Comment